Memo #210

By Lyle De Souza – ldesou02 [at] mail.bbk.ac.uk

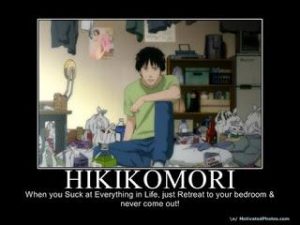

When the term “hikikomori” (引き籠もり, acute social withdrawal) was introduced by the Japanese media in the early 1990s, it referred to high school students or young adults. Government, academics and society blamed a range of social or cultural pressures that built up to breaking point (such as failing an exam). A government estimate in 2010 put the number of hikikomori at 700,000, though the actual figure may be far higher. Hikikomori are predominantly males from middle- or high-income families able to support them financially. Many of the first to withdraw over twenty years ago are now middle-aged and present Japan with a new set of social problems.

When the term “hikikomori” (引き籠もり, acute social withdrawal) was introduced by the Japanese media in the early 1990s, it referred to high school students or young adults. Government, academics and society blamed a range of social or cultural pressures that built up to breaking point (such as failing an exam). A government estimate in 2010 put the number of hikikomori at 700,000, though the actual figure may be far higher. Hikikomori are predominantly males from middle- or high-income families able to support them financially. Many of the first to withdraw over twenty years ago are now middle-aged and present Japan with a new set of social problems.

The reintegration of hikikomori becomes less likely the longer they have been withdrawn. For middle-aged hikikomori, the likelihood of gaining meaningful employment and re-entering society is very slim. A further problem looms when their parents who currently financially support them start to die. Who will then take care of hikikomori? When this eventually happens there may be an increase in suicides or violence by hikikomori forced to suddenly change their lifestyle.

The solutions at first seem daunting but there is hope. If Japan’s society, culture or education systems are the root causes these are not going to change overnight. Diagnosing hikikomori as a pervasive developmental disorder (PDD) is a first step towards recognition and description of the problem. However, PDD does not explain all instances of hikikomori, so more research needs to be done looking at gender roles, social class and societal expectations. Social workers or psychologists able to recognise hikikomori as a product of social change interacting with psychological processes have been successful in helping some hikikomori overcome their social anxiety. Some of the best results have been achieved with the recruitment of ex-hikikomori “rental brothers” who gradually build the confidence of hikikomori and offer them the hope that their predicament need not be a lifelong one.

Whether or not this is a peculiarly Japanese problem as society changes with a new global economy, the government urgently needs to direct resources towards these promising remedies as well as into further research.

About the Author:

Lyle De Souza is a visiting scholar at the Centre for Japanese Research, UBC. His research interests include Japanese cultural studies and literature of modern Japanese diasporas.

Links:

- Shutting Themselves In. The New York Times, 2006.

- Hikikomori, a Japanese Culture-Bound Syndrome of Social Withdrawal?The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 198, 444–449, 2010.

- French researchers seek raison d’etre of hikikomori. The Japan Times Online, 2011.

- Unable to conform, unwilling to rebel? youth, culture, and motivation in globalizing japan. Front. Psychology 2, 207, 2011.

- Hikikomori: Adolescence without End. Univ Of Minnesota Press. Tamaki, S., 2013. (Forthcoming).

Related Memos:

- See our other memos on Japan

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.