Memo #384

By: Andrew Chubb – achubb [at] gmail.com

The significance of Western media coverage of the Democracy Wall Movement in China for the present.

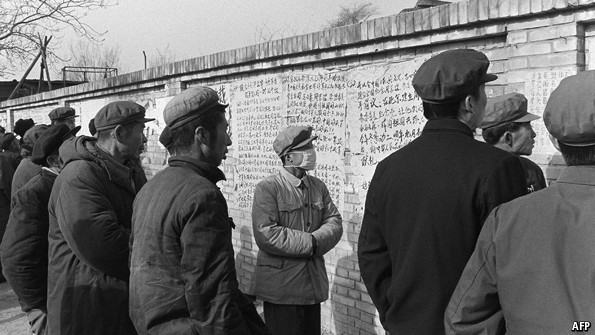

Between November 1978 and April 1979, Chinese citizens took to putting up wall posters on the streets of various cities in China, airing Cultural Revolution grievances, and calling for the relaxation of the country’s stifling ideological atmosphere. In Beijing, a stretch of wall on Chang’an Boulevard earned the name, “Xidan Democracy Wall,” and became emblematic of a brief window of free expression in China. Why is this event from decades ago significant today?

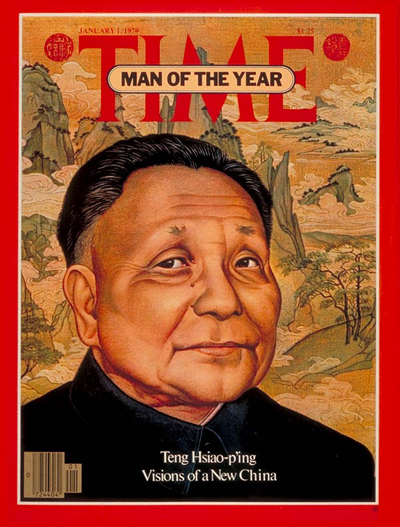

First, the movement left a major, ongoing political-historical legacy. Not only was it the first spontaneous free speech movement since the founding of the People’s Republic, it helped consolidate the power and the overseas image of the man on whose authority China’s reforms in the post-Mao period were implemented — Deng Xiaoping. Deng initially supported the movement, asserting that it demonstrated the freedom and democratic awareness of the masses, and the stability of Chinese state and society. Participants in the Democracy Wall movement generally did not seek to challenge the Chinese Communist Party’s authority, but Deng used the protests to delegitimize individual political opponents. He also used it to present an image of himself as a champion of social progress and democracy that accorded with American values and ideology; this in turn contributed to rapid normalization of Sino-American relations in 1979.

Second, the case revealed the complex effects that foreign media coverage can have on domestic political developments. The international media’s coverage of events in China in 1978-79 contributed to a negative radical flank effect, under which extreme elements of a social movement can increase the incentives for state suppression of the movement in general. The Western media’s focus on its most radical positions contributed to Deng’s eventual designation of the movement as a threat to stability and party rule. Arrests begun in March 1979. As the Arab Spring reaffirmed, the relationship between social movements and international media remains pivotal today, even in the age of social media and self-broadcasting. The Democracy Wall episode provides a cautionary example for social activists seeking to harness the power of media, and a basis for ethical practice for journalists seeking to understand the range of possible consequences of their standard reporting practices.

About the Author:

Andrew Chubb is a PhD candidate in political science and international relations at the University of Western Australia, studying the relationship between domestic Chinese public opinion and PRC foreign policy.

Beijing, 1979. (Source: AFP via The Economist)

Cover of Time Magazine. January 1, 1979 issue. (Source: Time)

Links

- Andrew Chubb, “Democracy Wall, Foreign Correspondents, and Deng Xiaoping,” Pacific Affairs 89, no. 3 (2016): 567-589.

- Yu Guangyuan, 1978: Wo qinli de na ci lishi zhuanzhe [1978: that historical turning point I personally experienced] (Beijing: Zhongyang bianyi chubanshe, 2008). Translation of 2001 edition by Steven Levine.

- Hu Jiwei, “Hu Yaobang yu Xidan minzhu qiang” [Hu Yaobang and the Xidan Democracy Wall], Zhengming, April 2004, accessed 9 May 2016. Translation by Andrew Chubb.

- Documents and photographs of the Democracy Wall movement, curated by Helmut Opletal at the University of Vienna.

- David Goodman, Beijing Street Voices (London: Marion Boyars, 1981).

Related Memos:

See our other memos on China.