Memo #188

By Rian Thum – thum [at] loyno.edu

Among the numerous cultural restrictions aimed at China’s Uyghur population, the Chinese government focuses particularly intently on control of religious activities. This past Ramadan saw an increase in state-imposed restrictions on ordinary Islamic practices among the Uyghurs. Since Beijing proclaims support for a distinct Uyghur identity while suppressing Islamic practices, it is worth reconsidering the historical connections between identity and Islam among the Uyghurs and their ancestors.

Among the numerous cultural restrictions aimed at China’s Uyghur population, the Chinese government focuses particularly intently on control of religious activities. This past Ramadan saw an increase in state-imposed restrictions on ordinary Islamic practices among the Uyghurs. Since Beijing proclaims support for a distinct Uyghur identity while suppressing Islamic practices, it is worth reconsidering the historical connections between identity and Islam among the Uyghurs and their ancestors.

Although the people known today as Uyghurs only adopted their current ethnic name in the early 20th century, many of their 19th century ancestors also saw themselves as a distinct group. To distinguish themselves from their neighbours, they usually called themselves “Musulmanlar” (Muslims), and sometimes referred to their language as “Musulmanche” (Muslimese). These terms were used even to distinguish themselves from other Muslims, like Muslim Kirghiz groups or the Sino-Muslims.

And how did these “Musulmanlar,” living separately in oasis towns scattered around the enormous Taklamakan desert, develop a shared sense of group identity? Common rituals and sacred texts helped form bonds between the “Musulman” oases.

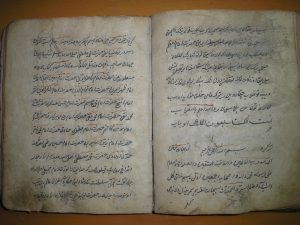

Ordinary people made pilgrimages to the tombs of local saints, often crossing hundreds of kilometres of desert to visit the famous saint of a distant oasis. At the tombs, pilgrims listened to readings of the saints’ biographies, i.e. their neighbours’ local history. Thanks to the dominance of manuscript technology, which allowed individuals to customize their own books, such histories were easily combined into larger volumes that provided a shared history for the “Musulmanlar,” a history based on the lives of Islamic saints.

In other words, we might say from a modern perspective that the local form of Islam played a central role in interconnecting the oases of the “Musulman” homeland – today’s southern Xinjiang. It was not the reformist Islam that Beijing fears today, but instead a distinct local expression that venerated local holy figures like the “Seven Muhammads” of Yarkand and the warrior-king Ali Arslan Khan of Kashgar.

These mechanisms survive among the Uyghurs only in greatly transformed customs. But they remind us that separating Islam and Uyghur identity may not be as easy as recent Chinese policy seems to presume.

About the Author:

Rian Thum is Assistant Professor of History at Loyola University New Orleans.

Links:

- Modular History: Identity Maintenance before Uyghur Nationalism, Journal of Asian Studies, August 2012.

- Beyond Resistance and Nationalism: Local History and the Case of Afaq Khoja, Central Asian Survey, October 2012.

- The Ethnicization of Discontent in Xinjiang, The China Beat, October 2, 2009.

Related Memos:

- Our other Memos about China