Memo #274

By Yves Tiberghien – yves.tiberghien [at] ubc.ca

India and Indonesia are both facing crucial elections this year: May for India and July for Indonesia (April for parliament). Although contexts are different and their ties are rarely explored, they face remarkably similar economic issues. Both are seen as successful emerging powers of the 2000s and powerful members of the G20. Yet, in both cases, the public is tired of ineffective public policy, major bottlenecks, and corruption. In both, there is hope that a providential new leader will launch a new wave of key reforms and move the nation to a new stage of growth.

India and Indonesia are both facing crucial elections this year: May for India and July for Indonesia (April for parliament). Although contexts are different and their ties are rarely explored, they face remarkably similar economic issues. Both are seen as successful emerging powers of the 2000s and powerful members of the G20. Yet, in both cases, the public is tired of ineffective public policy, major bottlenecks, and corruption. In both, there is hope that a providential new leader will launch a new wave of key reforms and move the nation to a new stage of growth.

At the root of these parallel trajectories lies one similar reality: according to World Bank figures, in 2012, Indonesia’s GDP per capita in PPP terms reached $5,000 and India’s reached $4,000. This compares to China’s $9,200. Both Indonesia and India find themselves right at the center of the so-called “middle income trap.” In other words, their remarkable, nearly 15-year trajectory of high-speed growth, based on an extensive model with high labor influx and high capital use, is reaching its limit.

They will only be able to unlock the next stage of growth and move from lower-middle income to upper-middle income and beyond if they start increasing productivity and move up the value added ladder. This requires investment in manufacturing and technology. To get there, the government must invest in infrastructure and institutions that will make such an upgrade possible. It is also crucial that they invest in human capital formation and higher education.

All this requires more accountable, inclusive, and clean governance. Development patterns from over 100 countries over the last 50 years tell us that countries have no more than a 20-year window to make this institutional transformation. The alternative is to remain stagnant at the level reached.

Indonesia is currently placing its hopes in the youthful new governor of Jakarta, Joko Widodo (“Jokowi”), while India’s election is likely to see the decimation of Congress in the forthcoming May election and the coming to power of reform-minded Bharatiya Janata Party led by Narendra Modi. Both men are in a hurry and both come with drawbacks. But the electorates of both countries understand that the stakes are high.

About the Author:

Yves Tiberghien is the Director of the Institute of Asian Research and Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of British Columbia; Executive Director of the China Council, and a Senior Fellow with the Global Summitry Project at the Munk School, University of Toronto.

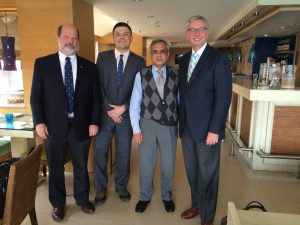

On February 18, UBC President Toope (far right), UBC Vice President John Hepburn (far left), and IAR Director Yves Tiberghien (second left) met in Delhi with Dr. Rajiv Kumar, a senior leader of the think tank Centre for Policy Research (http://www.cprindia.org), to discuss India’s economic reforms and foreign affairs.

-

Links:

- Pew Global, “Indians Want Political Change,” February 2014

- World Bank, “China 2030: Building a Modern, Harmonious, and Creative Society,” 2013

- Rhee Changyong (Asia Development Bank), “Indonesia risks falling into the middle-income trap,” Jakarta Globe, March 2012

- Jesus Felipe (Asia Development Bank), “Tracking the Middle-Income Trap: What is It, Who is in It, and Why?” (Part 1) (Part 2), 2013

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.