Memo #397

By: Kelvin E.Y. Low – kelvinlow [at] nus.edu.sg

In 2008, the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) of Singapore announced that its conservation program would extend beyond buildings to include other landmarks and structures such as bridges, pavilions, and towers that were emblematic of the nation’s history and heritage. Such conservation efforts were to be administered alongside the 6,800 buildings that had been gazetted for conservation from three decades ago. Recently, old shophouses, the National Stadium, Singapore’s oldest bus stop that has catered to generations of military servicemen, and playgrounds in housing estates built in the 1970s have likewise received heritage attention. While buildings and other landmarks were conserved as heritage icons, this also marked the designation of particular routes as heritage trails.

So why is extending designation beyond sites and buildings, to routes and trails significant? Heritage sites and trails form intersections between collective histories and individual biographies, and also serve as visual and experiential reminders of how Singapore society has progressed through the decades. By walking and moving through specific trails that are invested with sensory cues that conjure the past, and textured with individual stories and experiences that have transpired at specific sites, tourists and locals can consume through senses beyond sight relations to place and history. Trails of course still bring visitors to visible sites that serve as heritage icons which include art deco buildings and bridges. But beyond sights, trail guides and trail signs explain local food histories and possible dining experiences for walkers. For example, in the Jalan Besar Trail brochure, brief histories of nipah and opeh bring to life the dynamics of everyday gastronomy:

Nipah is a mangrove plant with the oldest known fossil pollen dating back to 70 million years. Its fruit is the attap chee that Singaporeans are familiar with in ice kachang.

Opeh, the beige, fibrous sheet used as a wrapper for takeaway food in the past, comes from the betel nut palm, a tree that grows in the hot and humid tropics.

Heritage trails therefore provide figurative and literal avenues through which the past is engaged through embodied ways that are further bolstered by multiple sensory encounters. As heritage continues to receive attention from policy makers and the public, producing new ways to understand and consume collective history requires long-term planning and inclusion of different stakeholders together to produce new roots and routes of belonging and community, for both visitors and locals.

About the Author:

Kelvin Low is Associate Professor and Deputy Head at the Department of Sociology, National University of Singapore.

Toa Payoh is home to Singapore’s first Housing Board estate, and as seen on the picture above, the 1973 Southeast Asian Peninsular Games athlete village. (Credit: The Straits Times via IfOnlySingaporeans.blogspot)

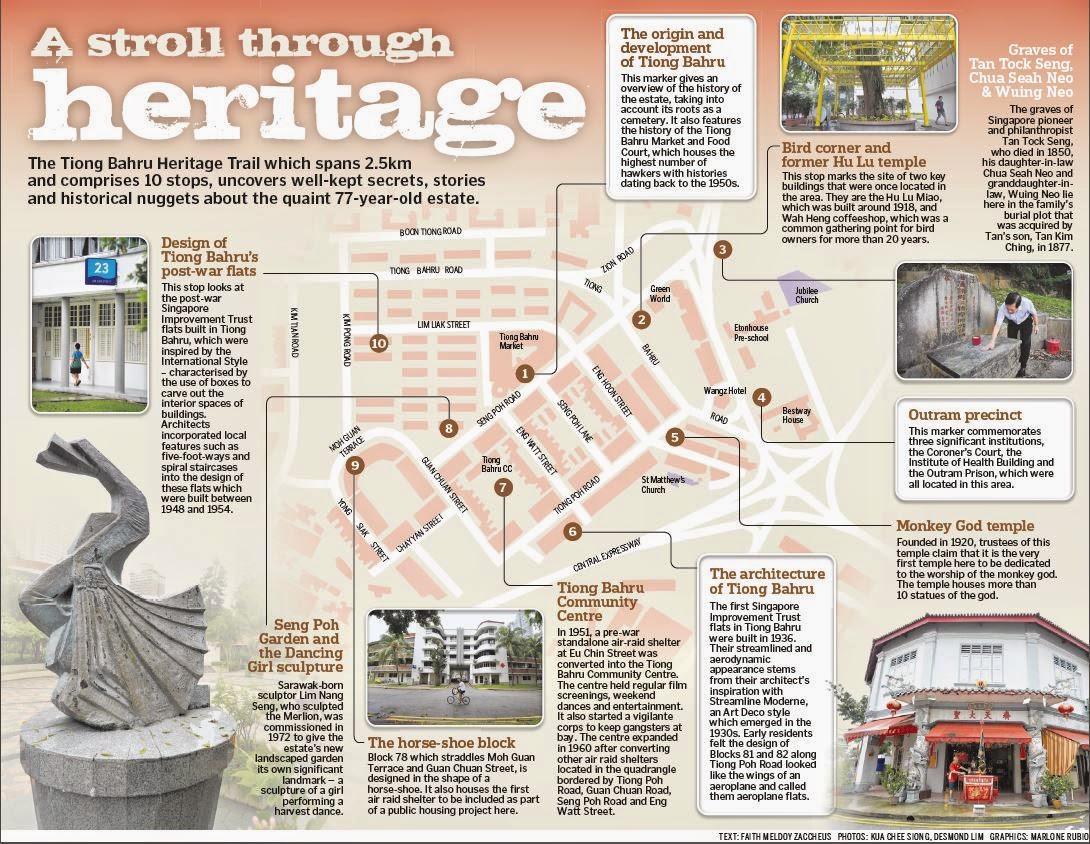

Infographic created for the Tiong Bahru Heritage Trail. (Credit: The Straits Times via Cheekie Monkies)

Links

- Kelvin E.Y. Low, “Concrete Memories and Sensory Pasts: Everyday Heritage and the Politics of Nationhood,” Pacific Affairs 90, no. 2 (June 2017), forthcoming issue.

- Joan Henderson, “Understanding and using built heritage: Singapore’s national monuments and conservation areas,” International Journal of Heritage Studies 17, no. 1 (2011): 46-61.

- Sidney Cheung, and Chee-Beng Tan, eds., Food and Foodways in Asia: Resource, Tradition and Cooking (London: Routledge, 2007).

Related Memos:

See our other memos on Singapore.