Memo #231

By Glen Hamburg – glenhamburg [at] gmail.com

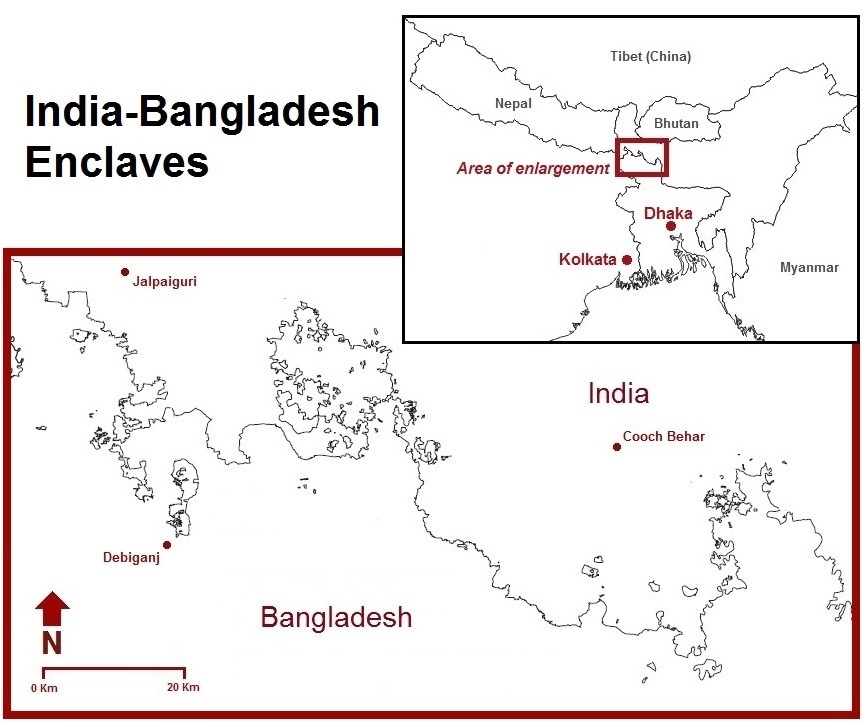

An international enclave is a piece of one state’s sovereign territory entirely surrounded by the territory of just one other state. Nearly 200 such land-locked islands lie along India’s border with northern Bangladesh. The obscure remnants of eighteenth century tax arrangements, these enclaves (chhitmahals in Bengali, the local language) have long challenged India-Bangladesh relations and threatened the well-being of the estimated tens of thousands of people who live in them.

An international enclave is a piece of one state’s sovereign territory entirely surrounded by the territory of just one other state. Nearly 200 such land-locked islands lie along India’s border with northern Bangladesh. The obscure remnants of eighteenth century tax arrangements, these enclaves (chhitmahals in Bengali, the local language) have long challenged India-Bangladesh relations and threatened the well-being of the estimated tens of thousands of people who live in them.

Life in the chhitmahals is bleak; inaccessibility has prevented the construction of medical facilities, sanitation infrastructure and schools within the enclaves, and because their territory cannot be accessed by law enforcement agents, they have often served as bases for drug and human trafficking. Their geographically-isolated residents generally do not possess official identification documents, in part because they are not permitted to transit across the surrounding foreign territory to access the offices in which these are issued. Chhitmahalis are thus unable to prove their citizenship, cannot vote and are effectively rendered stateless.

The leaders of India and Bangladesh agreed in 1974 to dissolve the enclaves by transferring their disconnected pieces of territory to the respective country in which they lie. The accord, known as the Land Boundary Agreement (LBA), was immediately ratified by Bangladesh’s parliament, yet India has waited decades to do the same. Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh re-stated his country’s commitment to implementing the accord in a visit to Bangladesh in 2011.

That promise still has not been fulfilled. Opponents in India generally say they are against the LBA’s implementation because their country would not be compensated for its net loss of some 40-square kilometers of territory to Bangladesh. However, the enclaves have served as a bargaining chip for Indian politicians in unrelated domestic and international contests over natural resources, business interests, migratory rights, regional security, group identity and electoral advantage.

Such side issues stymied the latest attempt to ratify the LBA and dissolve the enclaves this May when India’s Minister of External Affairs was physically prevented from introducing the necessary bill in Parliament. Nearly four decades since India ostensibly agreed to transfer the enclave territory, the world’s most complex border – and the tragic conditions it creates – remains unchanged.

About the Author:

Glen Hamburg is studying for the MA in Asia Pacific Policy Studies at the University of British Columbia, and is currently a visiting research scholar at the Institute of Foreign Policy Studies, Kolkata, India.

The author with residents of residents of Dahala Khagrabari #47, an Indian enclave inside Bangladesh.

Links:

- Scuffle in Rajya Sabha over land boundary bill, Times of India, May, 2013

- R. Jones. (2009). Sovereignty and statelessness in the border enclaves of India and Bangladesh. Political Geography, 28, 373-381. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2009.09.006

- W. van Schendel. (2002). Stateless in South Asia: the Making of the India-Bangladesh Enclaves. The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 61, No. 1, 115-147. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2700191

Related Memos:

- See our other memos on India and Bangladesh

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.