Memo #383

By: Wei Lit Yew – wlyew2-c [at] my.cityu.edu.hk

Where does Malaysia stand in the face of rising activism?

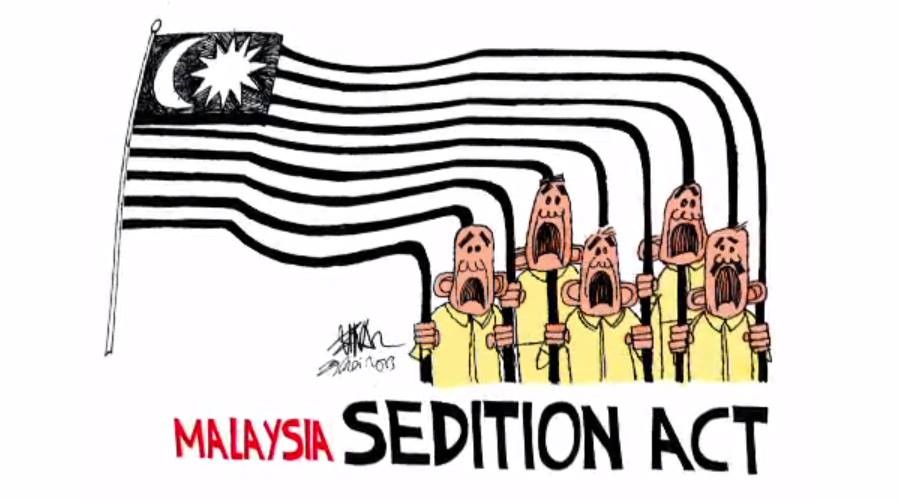

2013 marked the point at which the Barisan Nasional (National Front, BN) coalition government of Malaysia began constricting political space, after experiencing its worst electoral performance in its history. In 2015, the number of people investigated, charged, and convicted under the draconian Sedition Act totalled 220 – a quintuple rise from the previous year. The repressive trend continued in 2016, as opposition leaders and political activists endured thus far the worst of state intimidation.

2013 marked the point at which the Barisan Nasional (National Front, BN) coalition government of Malaysia began constricting political space, after experiencing its worst electoral performance in its history. In 2015, the number of people investigated, charged, and convicted under the draconian Sedition Act totalled 220 – a quintuple rise from the previous year. The repressive trend continued in 2016, as opposition leaders and political activists endured thus far the worst of state intimidation.

The Penang Chief Minister and prominent opposition leader Lim Guan Eng has been accused of graft, with the possibility of imprisonment depending on the High Court’s decision. The BN had already used this tactic to imprison another opposition party leader, Anwar Ibrahim. Just as several foreign political activists were denied entry into Malaysia, the chairperson of Bersih (Malaysia’s electoral reform movement) was barred from travelling overseas. The state similarly views student activism as particularly menacing. A university student convicted of sedition was originally sentenced to one year in prison, before successfully appealing for a reduced sentence of a RM5,000 (USD$1,237) fine.

However, the repressive patterns remain contingent on activist categories. For example, although environmental activists have suffered from police intimidation and arrests, it has been less systematic. Rather, they tend to confront subtler tools of state control, including being surveilled by the police intelligence unit. The activists who resisted a rare earth refinery plant, for example, experienced multiple arbitrary delays in their lawsuit against the government and application for public event permits. But because the mobilizational cause is not unambiguously political, activists can largely operate within a confined space, and occasionally pressure for government concessions. For instance, the five-year struggle against a dam project in Sarawak state paid off, when the government cancelled it earlier this year.

Evidently, though the BN government has weakened and suffered internal squabbles since 2013, it remains atop a robust state apparatus that enables the use of both harsh and subtle tactics against oppositionists and activists. The sophisticated deployment of the law and its bureaucratic apparatus has allowed the government to appear “urbane,” even while state oppression has ramped up.

About the Authors:

Wei Lit Yew is a PhD candidate at the Department of Asian and International Studies, City University of Hong Kong.

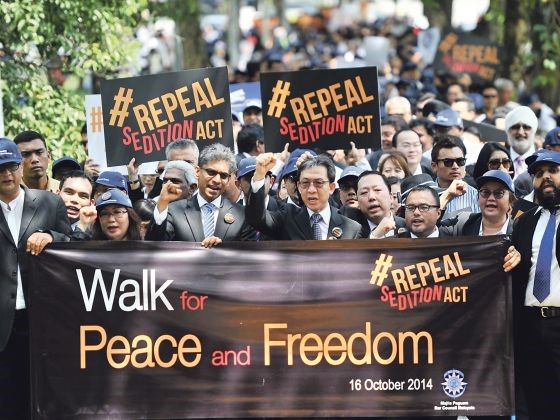

More Than 500 Lawyers Marching Against Sedition Act In Kuala Lumpur On October 16, 2014. (Credit: The Malay Mail/Today Online)

Cartoon By Malaysian Artist Zunar Who Was Also Charged With Nine Counts Of Sedition. (Credit: Zunar Via Hakam.Org)

Links

- Wei Lit Yew, “Constraint without Coercion: Indirect Repression of Environmental Protest in Malaysia,” Pacific Affairs 89, no. 3 (2016): 543-565.

- “Lim Guan Eng claims trial to 2 corruption charges”, The Borneo Post, June 30, 2016.

- Human Rights Watch, “Creating a Culture of Fear: The Criminalization of Peaceful Expression in Malaysia,” 27 October 2015.

- International Rivers, “Baram Dam Stopped! A Victory for Indigenous Rights,” 22 March 2016.

- SUARAM, “SUARAM Human Rights Report Overview 2015,” 9 December 2015.

- Jothie Rajah, “Punishing Bodies, Securing the Nation: How Rule of Law Can Legitimate the Urbane Authoritarian State,” Law & Social Inquiry 36(4), 2011.

- Meredith L. Weiss, Student activism in Malaysia: Crucible, mirror, sideshow, Cornell Southeast Asia Program Publications; NUS Press, 2011.

Related Memos:

See our other memos on Malaysia.

Malaysia I think has its own historical dynamics, through which its institutional problems linger on. There would be few countries, though, that are immune to world trends. Some of these are favourable. The idea that there could be war between almost any of the OECD countries is now absurd, which is a tremendous development of the last few decades. War, even civil war, has now become much less prevalent also in most developing regions. There has also been significant – but no, not enough – progress on some environmental matters. New renewables have gone from nothing to, well, something, and a subsantial something in some regions.

Human rights have experienced a more mixed fate. There has been some progress for indigenous peoples, the disabled, women and other than heterosexual people. But there have been some setbacks, both instigated and inspired by two sources. One, a breakout from certain dissatisfied rulers nostatlgic for absolute power. The figure-head for these is obviously VVP. Some of those inspired to follow his path are the late Hugo Chavez, the current Lord High Butcher of Manilla and even the current Chinese leadership. Strange to say, that last, because China has long had an overtly fascist regime, far worse than anything dreamed up even by Putin. However, it’s a matter of political relativity and a question of direction.

The other source is, broadly, the developed world, in particular the USA; countries that mostly like to claim some credit for socio-political sophistication and humaneness. These have of late too often been more openly ready to cash in their credibility for perceived short-term gain. In the case of the US, there has been the frank adoption of torture in interrogation, the entanglement of allied nations in degrading violations of human rights, such as with rendition, and the refusal to prosecute their own military personnel in cases of blatant war crimes.

Another major and accelerating human rights setback over the last two or three decades has been the gradual repudiation of established international law on the rights of refugees. Australia has shamefully been perhaps the number one perpetrator and example here, with its construction of refugee concentration camps, first in the desert, then on its own remote islands and finally on foreign islands – Nauru and Manus Island (PNG), being content in the process to corrupt the institutions of those impoverished countries and disembowel their social harmony. Australia has also pioneered an array of barbarities with its “on water” practices and its mainstream public discourse, demonising refugees. Many of these practices and epithets have been adopted in Europe.

Countries like Malaysia have to sort out their own problems, but a poisonous international milieu doesn’t help. There was a time when a French/German government, experiencing some difficulties, might say, “hey, let’s go to war with Germany/France. Now , that is seen to be ridiculous. Perhaps some of us will live to see the day when it will also become ridiculous in Sri Lanka, Malaysia, Venezuela, Singapore, Zimbabwe or Belarus for a government in difficulty to say, “hey, let’s arrest some of the opposition and harass some student activists.”