Memo #182

Featuring Christopher Rea – chris.rea [at] ubc.ca

Mo Yan (Guan Moye, 管谟业, b. 1955) has been one of China’s best-known fiction writers since the 1980s. He is of the generation that was in their teens during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), and many of his stories deal with issues of historical violence, political abuses, and bodily trauma, particularly in rural China. His most famous novels include Red Sorghum (1988), which was adapted into a film by Zhang Yimou, The Garlic Ballads (1989), Republic of Wine (1992), Big Breasts and Wide Hips (1996), and Life and Death are Wearing Me Out (2006). One of his latest is Frog (2009), an epistolary novel that deals with China’s one-child policy.

Why did this year’s Nobel Prize in Literature go to him?

For several reasons; I’ll mention just a few. First and foremost, it’s a lifetime achievement award for a writer who has developed a distinctive literary voice over decades of relentless stylistic innovation and experimentation. Second, excellent translations exist of most of Mo’s major works. Howard Goldblatt is to thank for having made him a viable candidate for this and other international prizes. Third, Mo Yan is a known quantity; he’s been endorsed by other Nobel Laureates and won several major awards. His prize is also a capstone to the career of Göran Malmqvist, a member of the Swedish Academy who has been a tireless champion of Chinese writers and is 88 this year.

Are there other Chinese writers who you think deserve the Prize?

Among fiction writers, I admire Su Tong, who might be a viable candidate in several years’ time provided that he is not considered to be too similar to Mo Yan. Pai Hsien-yung, who was born in mainland China but grew up in Taiwan, is one of my favourite stylists, but his chances are slim both because of his age and because his oeuvre of stories and novels is small. Both sides of the Taiwan Strait have a number of talented novelists, essayists, and poets writing in Chinese who deserve a broader international readership, so I think that we’ll see more Sinophone contenders in the future.

The Republic of China: Restoring a Father’s and a Nation’s Life Story (Memo #167 on Pai Hsien-yung)

What is the significance of Mo Yan’s award?

Commentators will no doubt couch it in terms of the current media discourse about “soft power” and “China’s rise.” China’s global visibility is important both to Mo’s selection and to the national pride it has generated. To me, however, the most pertinent question is when we’ll have non-Chinese writers crediting Mo Yan and other Chinese writers as a stylistic influence. Right now, Mo Yan has to be explained to international readers in terms of Faulkner or García Márquez. Mo’s prize is important because it puts Chinese writers on the map in a way that – fairly or unfairly – Gao Xingjian’s, who was a French citizen when he won it in 2000, didn’t.

What effect will Mo’s prize have on the Chinese literary field?

The overall effect should be positive. It is a tremendous morale boost to Chinese writers, since it confirms decades of critical praise of Mo Yan in his home country. Though deeply influenced by foreign writers, he embodies literary values cherished in the PRC, such as writing about the sufferings of common people. More international attention will be paid to Chinese writers, resulting in more translations, which is great. The Prize may inspire some Chinese writers to imitate the Mo Yan model of hefty novels that explore violence of Chinese history with surrealist humour and local colour. My hope is that it encourages not mimicry but more stylistic experimentation.

Which of his novels would you recommend to a first-time reader?

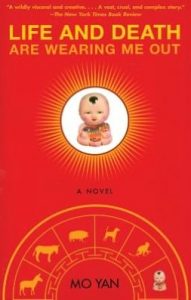

Republic of Wine is a trip – a mix of detective novel, political allegory, authorial self-interrogation, and carnivalesque fantasy threaded with leitmotifs of inebriation and cannibalism. Life and Death are Wearing Me Out is one of Mo’s funniest works, in which a villager undergoes successive reincarnations as a donkey, ox, pig, dog, monkey, and “big-headed” boy. Each chapter takes a different bestial perspective on modern Chinese history, beginning with the 1950s Land Reform. Red Sorghum focuses on horrors in the countryside during the Republican period and the Japanese invasion. For quicker reads, try the stories in his collection Shifu, You’ll do Anything for a Laugh.

About the Interviewee:

Christopher Rea is an Associate Professor of Modern Chinese Literature in the Department of Asian Studies, The University of British Columbia.

Links:

- China’s Nobel Prize Complex, circa 1946, The Toronto Star, December 2010. (By Christopher Rea).

- China ‘vindicated’ by Mo Yan’s Nobel literature prize, Radio Australia, October 2012. (Featuring Christopher Rea).

- Excerpt: Nobel Winner Mo Yan’s ‘The Republic of Wine’, The Wall Street Journal, October 2012.

- Exclusive Excerpt: Nobel Winner Mo Yan’s ‘Sandalwood Death‘, The Wall Street Journal, October 2012.

- Forthcoming in December 2012 from University of Oklahoma Press: “Sandalwood Death.”

Related Memos:

- Our other Memos on China.