Memo #330

By Fen Lin – fenlin [at] cityu.edu.hk

Peking University, the traditional locus of Chinese liberalism, seems to be yielding this role to China’s economics and financial universities. A 2012 survey, conducted among six elite universities in Beijing and Shanghai, revealed that only 14% of Peking University students described themselves as liberal reformists, the lowest percentage among the six universities surveyed. However, some 21% of Shanghai University of Finance and Economics students claimed to be such.

Peking University, the traditional locus of Chinese liberalism, seems to be yielding this role to China’s economics and financial universities. A 2012 survey, conducted among six elite universities in Beijing and Shanghai, revealed that only 14% of Peking University students described themselves as liberal reformists, the lowest percentage among the six universities surveyed. However, some 21% of Shanghai University of Finance and Economics students claimed to be such.

Such a trend is a manifestation of the economic liberalism China has been pursuing for decades. After the suppression of the 1989 student movement, the most vocal and radical intellectuals who had contributed to the rise of pro-democracy consciousness were forced into exile or silenced. Not until policy makers and intellectuals reconciled over market reforms did the liberals again find their voices. The neo-liberalists of the 1990s advocated privatization, protection of property rights, public spending cuts, and the liberalization of trade and investment. Ever since, universities specializing in economics and finance have become popular choices among students. It follows that students from these universities would theoretically secure well-paying jobs upon graduation, and thus tend to favor economic liberalism and label themselves as liberals. China’s rapid socioeconomic transition is modifying the connotations of what it means to be liberal in China. Since 2004, the growth of nationalistic sentiment and its alliance with the New Left has further narrowed liberalism in the Chinese context to its economic dimension.

Compared with a 2007 survey that revealed 61% of students identifying themselves with liberalism, this 2012 survey seems to hint at the decline of liberalism in China. However, such a conclusion would be hasty, if not misleading. This survey also indicates that compared with other universities Peking University has the highest proportion of students (24%) who self-identify as “other” in terms of political orientation, thus refusing the binary categories of liberal and left/nationalist. Though many intellectuals reject such binary labels, they continue to use them for lack of better terminology, not having fully figured out a “Chinese alternative.”

If the 2012 student survey reveals anything it is that the current political outlook of Chinese elite students is characterized by a certain continuity with previous generations, but with a new complexity.

About the Author:

Fen Lin is an assistant professor of media and communication at the City University of Hong Kong. She co-authored, Communication, Public Opinion, and Globalization in Urban China (Routledge 2013).

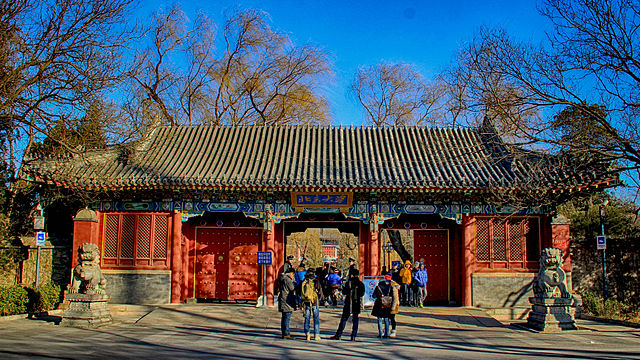

Peking University, once the bastion of student liberalism, is yielding this position to the country’s economics and finance universities. What does this tell us about the shifting and evolving nature of liberalism in China? (Credit: Wikicommons).

Links:

- Fen Lin, Yanfei Sun, & Hongxing Yang, “How are Chinese Students Ideologically Divided? A Survey of Chinese College Students’ Political Self-Identification,” Pacific Affairs 88-1 (March 2015)

- Joseph Fewsmith, China since Tiananmen: The Politics of Transition (Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2001)

- Merle Goldman and Edward Gu, eds. Chinese intellectuals between state and market (Routledge, 2005)

- Tianjian Shi, Jie Lu and John Aldrich, “Bifurcated Images of the U.S. in Urban China and the Impact of Media Environment,” Political Communication 28, no. 3 (2011)

- Susan Shirk, China: Fragile Superpower (Oxford University Press, 2007)

- Suisheng Zhao, A Nation-State by Construction: Dynamics of Modern Chinese Nationalism (Stanford University Press, 2004)

- Yongnian Zheng, Discovering Chinese Nationalism in China: Modernization, Identity, and International Relations (Cambridge University Press, 1999).

Related Memos:

See our other memos on China.

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.