Memo #400

By: Aim Sinpeng – aim.sinpeng [at] sydney.edu.au

Do social networking platforms like Facebook, Twitter or Firechat improve political participation among the previously disengaged? If so, do they transcend existing socioeconomic divides in political engagement? While some see the rise of online political engagement among youths in North America and Europe, whose participation in formal politics has long been in decline, as proof of the power of social media to draw new groups into political life, others are sceptical of the quality of participation, dismissing the data as reflective of a mere “clicktivism”. Moreover, there is concern that social media can in fact reproduce and even reinforce existing social biases in political participation. Empirical evidence on offline-versus-online political engagement during the 2013-14 political turmoil in Thailand indicates that Facebook can in fact bring new groups into politics and does not entrench participatory inequalities.

Thailand, which has witnessed prolonged political strife in the past decade, provides a fertile ground to investigate the impact of social media on political engagement. It is a highly unequal, digitally and politically divided society – which should make the use of social media for politics a luxury that only the middle and upper classes can afford. But a comparison of the socioeconomic and demographic profiles of the street protesters and Facebook supporters of two antagonistic movements – the United Front for Democracy against Dictatorship (UDD) and the People’s Democratic Reform Committee (PDRC) – during the 2013-2014 protests, demonstrates that street-level political participants from both sides of the political divide were better off and older than their Facebook peers. Those engaged in politics on Facebook have distinct socioeconomic backgrounds that are different from offline political participants, suggestive of a narrowing effect of participatory inequalities brought on by this social media platform.

Facebook profile analysis also provides evidence that challenges existing politico-economic explanations for the political polarization in Thailand, as it shows that both PDRC and UDD online supporters are from similarly lower levels of socioeconomic status. This diminishes the persuasiveness of prevailing accounts that invoke dichotomies of rich versus poor and urban versus rural as explanations, and provides grounds for intra-middle class explanations of the recent Thai political conflict.

About the Author:

Aim Sinpeng is a lecturer of comparative politics in the Department of Government and International Relations at the University of Sydney.

Demonstrators in Bangkok at a peaceful protest against Thailand’s controversial amnesty bill in November 2013. (Credit: Live Less Ordinary)

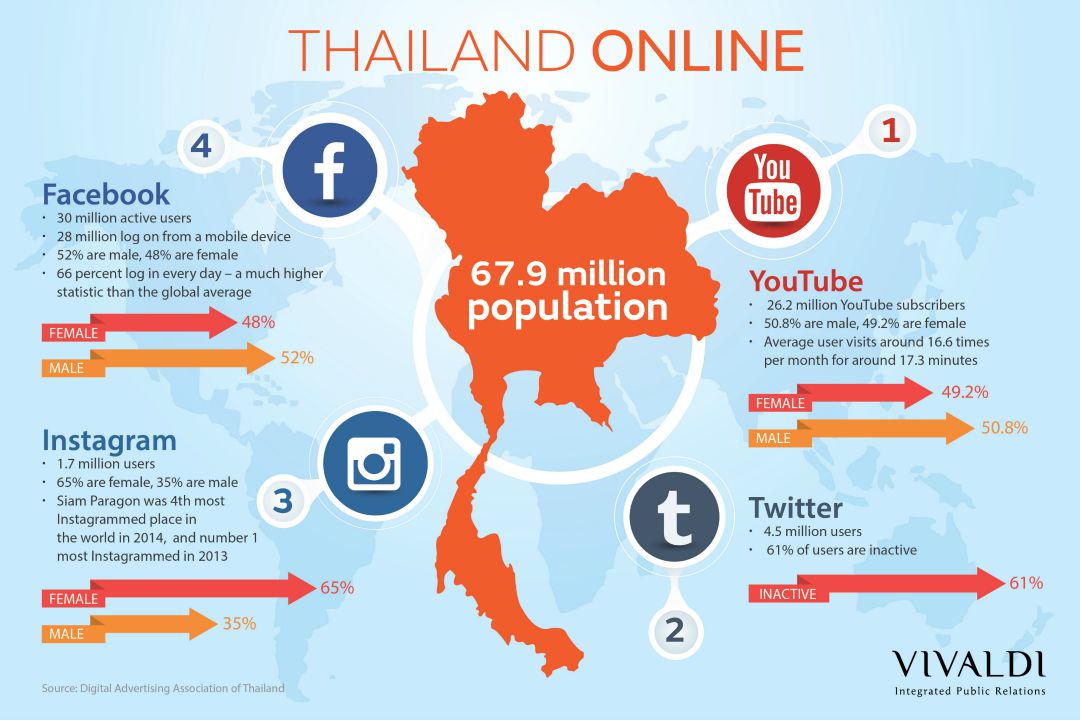

Infographic based on 2014 statistics from the Digital Advertising Association of Thailand. (Credit: Vivaldi)

Links

- Aim Sinpeng, “Participatory Inequality in the Online and Offline Political Engagement in Thailand,” Pacific Affairs 90, no. 2 (2017), forthcoming issue.

- Michael Xenos, Ariadne Vromen, and Brian D. Loader, “The Great Equalizer? Patterns of Social Media Use and Youth Political Engagement in Three Advanced Democracies,”Information, Communication & Society 17, no. 2 (2014): 151-167.

- Kay Lehman Schlozman, Sidney Verba, and Henry E. Brady, “Weapon of the Strong? Participatory Inequality and the Internet,”Perspectives on Politics 8, no. 2 (2010): 487-509.

- Jeff Fromm, “New Study Finds Social Media Shapes Millennial Political Involvement and Engagement,” Forbes (June 22, 2016).

- Jake Willis, “How Political Engagement on Social Media Can Drive People to Extreme,” The Conversation (July 21, 2015).

- Thitipol Panyalimpanun, “Facebook and Thai politics: Press ‘Like’, and hope for the best,” Asian Correspondent (July 7, 2015).

Related Memos:

See our other memos on Thailand.