Memo #360

By Robert S. Boynton – robert.boynton [at] nyu.edu

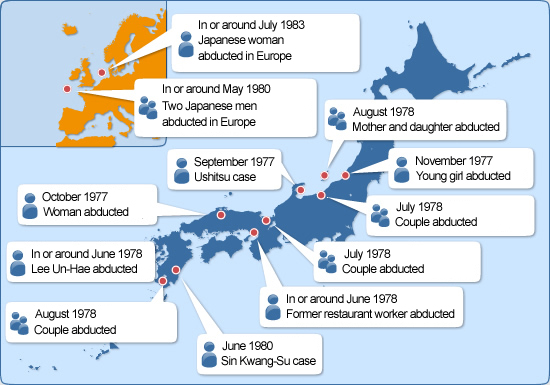

At the September 2002 Pyonygyang Summit between the heads of Japan and North Korea, Kim Jong-Il apologized to Koziumi Junichiro for some “rogue” North Korean agents that had abducted Japanese nationals during the 1970s and 1980s. This sparked saturation media coverage and amplified the voices right wing groups in Japan, which called for stronger measures against North Korea. In the aftermath of the summit, stranger-than-fiction accounts began to emerge of how North Korean agents had both abducted Japanese citizens from Japanese soil and lured them from Europe with false promises. Some of the surviving abductees, and the families they formed in North Korea, eventually made their way to Japan. But the fates of many other abductees remain unresolved as of 2016.

Drawing on a wide range of interviews, including with abductees, activists, politicians, and former government officials, Robert Boynton’s new book, The Invitation-Only Zone: The True Story of North Korea’s Abduction Project navigates a clear and cogent path through the complex twists and turns of the story. While the details of the experiences of the abductees, in particular, that of Hasuike Kaoru, form the core of the book, it also contains engaging accounts of the vexed history of Japan and the Korean peninsula.

The APM’s editor Hyung-Gu Lynn sat down virtually Robert Boynton to ask some questions on the process of research and writing his book.

Hyung-Gu Lynn (HGL): What got you interested in the subject of the abductions of Japanese nationals by North Koreans?

Robert Boynton (RB): I read about the abductions in a newspaper article on October 16, 2002, the day five of them were returned to Japan for a temporary visit. It was a year after 9/11 and I was relieved to find an international news story that had nothing to do with Afghanistan, Iraq or Bin Laden. I tried to learn more about the abduction, but the story pretty much disappeared from the Western media, which was focused on the War on Terror. Journalists often “collect string” on various stories that intrigue us, so I started a file on the abduction story. But I didn’t understand the scope and depth of the story until I first visited Japan in the spring of 2008 on a fellowship from the Japan Society.

HGL: Can you elaborate a bit more on the meanings of title of your book?

RB: When people first learn about the abductions of Japanese citizens, they assume that the abductees must have been kept in one of North Korea’s infamous gulags or prison camps. In fact, they lived in the various guarded communities in and around Pyongyang where the regime houses anyone who has access to information about the outside world, whether they are spies, translators, or abductees. They were called “Invitation-Only Zones,” the fiction being that one simply needed an invitation to enter them. If nothing else, North Koreans have an exquisite sensitivity to coded language, and didn’t require a “Keep Out” sign to know that this was a place they should avoid. As a student of Orwell, I, too, am very sensitive to how language is used, and the more I thought about it, I realized that North Korea is itself a kind of “Invitation-Only Zone”: a barely-functioning, hereditary, authoritarian state that struggles to appear like a “normal” modern nation.

A timeline overview of North Korean abductees from 1977 to 1983 (Credit: Headquarters for the Abduction Issue, Government of Japan).

HGL: You obtained interviews with a wide range of figures in Japan involved in the politics that led up to the 2002 Pyongyang Summit between Koizumi Junichiro and Kim Jong-Il. Were there any particularly challenging elements to obtaining access?

RB: People were generally eager to talk about the abductions, and were pleased that an outsider was taking an interest in them. Japan has made an enormous effort to draw the attention of the world to the abductions. My position as a professor, rather than a freelance journalist, helped me in a part of the world where teachers still have high status. However, some of those I interviewed were surprised that I returned to Japan again and again, digging deeper into an issue that they defined simply as a violation of Japan’s sovereignty and human rights. The abductions certainly were a violation of sovereignty and human rights, but I want to write a book that placed those violations in the larger context of the close relationship between Japan and the Korean peninsula, and the extraordinary cultural changes that modernity had forced on the entire region in the 19th and 20th centuries. I encountered a lot of resistance as I pursued these larger themes.

HGL: Did you find unexpected responses from any of the people you interviewed for the book? If so, can you elaborate?

RB: I was in Brooklyn, New York on September 11, 2001, and watched the twin towers fall. I was dismayed by the surge of nationalism the attacks inspired, and saddened by how effectively the terrorists tricked us into restricting the very freedoms that have made the U.S. a great country. In an odd way, writing about the abduction story, and my research on the history of North East Asia, helped me deal with America’s nervous breakdown. It provided a fascinating escape from the depressing events of the Bush years. So I was surprised when my Japanese friends told me that they thought of the abductions as “Japan’s 9/11.” This puzzled me at first, but as I witnessed the country redoubling its counterterrorism strategy and tightening its immigration controls, I began to understand that “Japan’s 9/11” was less an event than a state of mind. Like the U.S., Japan was traumatized by the sudden realization that the world was more dangerous than it had thought, a place where even the most prosperous and powerful nations are ultimately incapable of protecting themselves, whether from Al Qaeda or North Korea.

HGL: At the risk of being reductive, what is the one take-away point of your book?

RB: North Korea and Japan have a more intimate, complex relationship than either wants to admit, and the abductions are one of the tragic results of it.

About the Author:

Robert S. Boynton is the author of The Invitation-Only Zone: The True Story of North Korea’s Abduction Project (FSG, 2016) and The New New Journalism (Vintage, 2005) He directs NYU’s Literary Reportage program, and his articles have appeared in The New York Times Magazine, The New Yorker, The Atlantic, The Nation, and elsewhere.

Professor Robert S. Boynton’s newest book “The Invitation-Only Zone” was released in January 2016 (Credit: Macmillan Publishers).

North Korean abductees return to Japan September 15 2002 (Credit: AP / COURTESY FARRAR, STRAUS & GIROUX).

Links:

- Robert Boynton, “The Invitation-Only Zone: The True Story of North Korea’s Abduction Project” – official website of the book featuring press reviews, additional background information and more about the author.

- Linus Hagström & Ulv Hanssen, “The North Korean abduction issue: emotions, securitisation and the reconstruction of Japanese identity from ‘aggressor’ to ‘victim’ and from ‘pacifist’ to ‘normal’,” The Pacific Review, 28, no. 1 (2015): 71-93.

- Christopher W. Hughes, “‘Super-Sizing’ the DPRK Threat: Japan’s Evolving Military Posture and North Korea,” Asian Survey, 49, no. 2 (2009): 291-311.

- Hyung-Gu Lynn, “Vicarious Traumas: Television and Public Opinion in Japan’s North Korea Policy,” Pacific Affairs, 70, no. 3 (2006): 483-508.

- Brad Williams and Erik Mobrand, “Explaining Divergent Responses to the North Korean Abductions Issue in Japan and South Korea,” Journal of Asian Studies, 69, no. 2 (2010): 507-536.

- Hasuike, Kaoru, Ratchi to ketsudan (Abduction and Determination) – a memoir by one of the abductees, now a faculty member of Niigata Sangyo University 蓮池 薫『拉致と決断』新潮社, 2012 (Japanese).

Related Memos:

See our other memos on North Korea.