Memo#103

(The second Memo from the Theme, 100 Years after the Xinhai Revolution)

By Tsering Shakya – tsering.shakya [at] ubc.ca

The Xinhai Revolution of 1911 and the subsequent founding of the republic sought to remould China as being composed of five nationalities: Han, Manchu, Mongol, Tibetan, and Uyghur. This vision of a multi-ethnic nation had no appeal to Tibetans and Mongols. In divergent ways, the Xinhai Revolution created an opportunity for China, Tibet, and Mongolia to create a modern nation state.

The Xinhai Revolution of 1911 and the subsequent founding of the republic sought to remould China as being composed of five nationalities: Han, Manchu, Mongol, Tibetan, and Uyghur. This vision of a multi-ethnic nation had no appeal to Tibetans and Mongols. In divergent ways, the Xinhai Revolution created an opportunity for China, Tibet, and Mongolia to create a modern nation state.

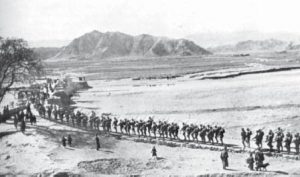

The revolution profoundly impacted China’s frontier regions. China’s authority disappeared, particularly from Tibet and Mongolia. Tibetans and Mongolians saw the overthrow of Manchu rule as an opportunity to free themselves from Qing colonialism. In the aftermath of the 1911 revolution, Tibet and Mongolia declared independence and became de facto independent states, remaining so until the mid-20th century. But only Mongolia achieved full recognition as a separate state while Tibet failed.

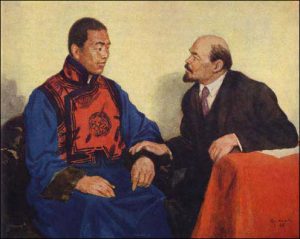

Independence from China brought Jazandamba, the Bodg Khan (spiritual and secular ruler), to power in a theocratic Mongolian government in the 1910s. Mongolian leaders shared the modernist goal of the Chinese revolutionaries and viewed traditional social structure as an impediment to modern nation status. Later Mongolian revolutionaries embraced the idea of the radical transformation of society and in 1921 became the first Asian country to declare a Communist revolution. Mongolia turned towards the Soviet Union in a strategic and ideological alliance.

Tibet, after expelling all vestiges of Manchu rule, became isolationist and any demand for social change was aggressively resisted. The death of the 13th Dalai Lama in 1933 left Tibet without leadership and plunged its ruling class into a power struggle, which further blinded them from developments occurring in China.

Between 1911 and 1949, the new regime in China was preoccupied with internal politics and faced resistance from Tibetans and Mongols. China was unable to reassert power in these two regions. Mongolia’s Communist revolution afforded Mongolians the protection of the Soviet Union and ensured its independence. Tibet remained independent of China’s rule between 1911 and 1950, although it never achieved de jure recognition.

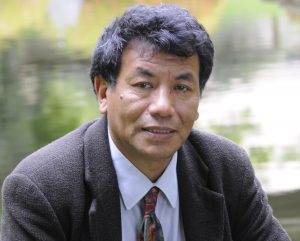

About the Author:

Tsering Shakya – CRC Chair in Religion and Contemporary Society of Asia, Institute of Asian Research, The University of British Columbia.

Mongolian People’s Republic. The meeting between D. Sukhe-Bator, the leader of the People’s Revolution of 1921, with V.I. Lenin in November, 1921

Links:

- Reins of Liberation, an entangled history of Mongolian independence, Chinese territoriality, and great power hegemony, 1911-1950 Book by Liu Xiaoyuan, 2006.

- Baabar, Twentieth Century Mongolia, Book edited by Chris Kaplonski, 1999.

- A History of Modern Tibet, 1913-1951: The Demise of the Lamaist Book by Melvyn Goldstein, 1991.

Related Memos:

- See Tsering Shakya’s Memo, Karmapa Controvery – Raid on a Tibetan Monastery in India (Memo #55)