Memo #365

By: Bruce and Ju-Chan Fulton – Bruce.Fulton [at] ubc.ca and ju.chan.fulton [at] gmail.com

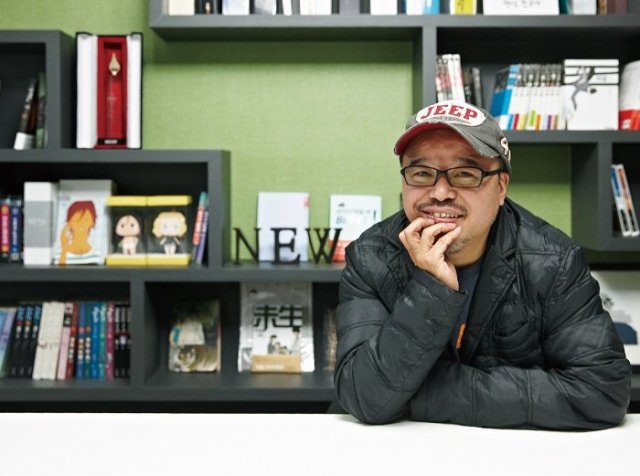

photo credit: SAM/KTLIT

With a domestic market estimated at well over 6 million individual readers per day and valued at over $300 million in 2015, South Korean webtoons have grown rapidly in scale and variety since their initial appearance on major search portal landing pages in the early-2000s. These vertical-scrolling digital comics have become a widespread form of entertainment for smartphone, tablet, and computer users, whether in the home, during the commute, or at work.

One of the most successful webtoon artists is Yoon Taeho, who has released several titles considered classics of the medium, including Misaeng (2012-13), The Insiders (2010-present), and his most famous work, Moss (Ikki, 2007-2009), an evocative, multi-layered, and piercing critique of the pervasive culture of violence and abuse that has stained South Korea’s contemporary political and social history. These three titles have been adapted for film (Moss and The Insiders) and television (Misaeng) to commercial success and critical acclaim.

Webtoons have been exported abroad on several platforms since 2014, with Japanese, Chinese, and English-language versions of Korean webtoon titles available, usually in a mix of free-to-view and paid-access models. The attempt to replicate domestic success for a wider, international readership requires not only appealing interface design, but also accurate, nuanced, and contextualized translations. Despite some developments in machine translation engines, such skilled translations remain rare even among human translators.

Yoon Taeho’s Moss has the good fortune to be translated by Bruce and Ju-Chan Fulton, an award-winning team widely acclaimed for their many translations of modern and contemporary Korean literature. The APM’s editor Hyung-Gu Lynn sat down virtually with Bruce and Ju-Chan Fulton to ask some questions about the process of translating Moss – currently serialized in English on Huffington Post.

Asia Pacific Memo Interview with Bruce and Ju-Chan Fulton

Hyung-Gu Lynn (HGL): How did you become involved in translating webtoons, or more specifically, Moss?

Bruce and Ju-Chan Fulton (BJCF): In our translation work we’re always on the lookout for ways to engage a broader audience with Korean literature, and Bruce’s teaching at UBC explores potential intertextual and intermedial links with Korean popular culture (Hallyu). For example, he uses Park Jiyoon’s Sŏnginshik (Coming-of-age ceremony) music video in his modern Korean literature survey course.

In the fall of 2009 Bruce met Yoon Taeho at UBC and he gave us a copy of Moss. We liked the plot and were fascinated by the images, especially Yoon’s drawing of eye movements. We saw in the story an allegory of abuse of power during the period of military dictatorship in the ROK, and Bruce thought it might prove useful in his teaching. So we obtained permission to translate one episode for trial use in class, and afterward Bruce canvassed his students and obtained an overwhelmingly positive response. So back we went to Yoon and his company and obtained permission to translate the entire five volumes for educational use.

Further, Yoon had virtually nothing in English translation, despite his considerable output over the previous two decades. That he remained virtually unknown in the English-speaking world reinforced in our minds the desirability of introducing him through a high-quality translation of one of his most important works.

And then last year, a further stroke of good luck. A Korean company, Rolling Story, packaged that work and some two dozen others and proposed them to the Huffington Post. Huffington Post accepted half a dozen works for serialization, including our translation of Moss. At the moment, about half of Moss has appeared, with a new installment published every Monday.

Yoon Taeho (credit: Lee Sang-sub/The Korea Herald)

HGL: There are several different views about the impact of medium, in particular how the mix of images and texts in comics, affects narrative, storytelling, and translation. Have you encountered any challenges in translating a webtoon that you might not have while translating literature?

BJCF: There are a variety of challenges. First of all, when we translate fiction we have physical control of the text and we can easily go back and forth between the original text and our translation. But in translating a webtoon we are working on an online platform that presents the Korean text and images on the left and only the images on the right, to which we add the English text. But because Yoon made some changes in the webtoon version prepared for on-line subscription and for the Huffington Post, we were essentially negotiating four texts: the initial 5-volume print version, a subsequent 4-volume print version, Yoon’s initial webtoon version, and finally the slightly modified webtoon version delivered to the Huffington Post.

Second, Moss is not an easy story to follow. Like much good fiction, and especially with works that involve political and social problems, there’s a great deal of hidden meaning. Bruce read through the 5-volume print version once, Ju-Chan read through this and the 4-volume print version a total of three times, and still we generated 9 pages of questions for the author, which we had an opportunity to discuss with him directly when he visited the University of Washington in March 2015. Questions continued to arise as we translated the entire work. Some of these we ran by Korean friends, and they too had difficulty understanding certain areas of the story.

Third, onomatopoeia was a constant challenge. The decision often involved whether to Romanize the Korean sound-words or to use English equivalents. For example, to represent the sound of a motor vehicle, both the engine and the wheels on the road surface, Yoon uses boooong. We utilized that Romanization, and then one of Bruce’s students asked why we didn’t use English vroooom instead. Another decision involved whether to translate Korean words that represent actions rather than sounds—for example hoek, which indicates a sudden movement.

Fourth, editing a webtoon translation is more of a challenge than editing a print translation. The text has to be consistent with the images, and most of the text we are translating is dialog rather than narrative. A further complication is that mistakes by the Rolling Story people in preparing the webtoon for the Huffington Post proved very difficult for them to correct. For example, in an early installment our “attorney at law” came out as “attorney at low.” Six months later, and in spite of half a dozen queries on our part, this mistake has not yet been corrected.

Finally, the greatest challenge, and perhaps the part of the process that offers the most satisfaction, is translating the dialog. Here, less is more, and there has to be rhythm and movement to the language.

Moss (Ikki) – Cover (credit: Yoon Taeho)

HGL: In connection with the question above, more specifically, have there been instances where you used the visuals or the images in assessing your translation of a particular dialogue or background sounds?

BJCF: Definitely. Especially during our editing (we would usually go through a batch of installments at least twice after completing a first draft) we would refer constantly to the images, and especially to the facial expressions of the characters—for example, to assess how strongly or how subtly to render the language in a particular dialog.

Many of the images are unaccompanied by dialog, and of course there’s the subtext that readers must grasp through the images alone. Our challenge was to convey the meaning to an audience that is not necessarily used to reading between the lines when they encounter a work of foreign literature. How much “dumbing down” should we be doing? This was a constant question. So we attempted to add cues that would help readers better understand the basic story line, as well as the cultural subtext.

Also, last fall we had an opportunity to share the Huffington Post translation to two classes at Seattle Central College, whom we asked to focus on the images with an eye to registering their engagement. We look forward to another opportunity later this year, at an anime conference in Seattle.

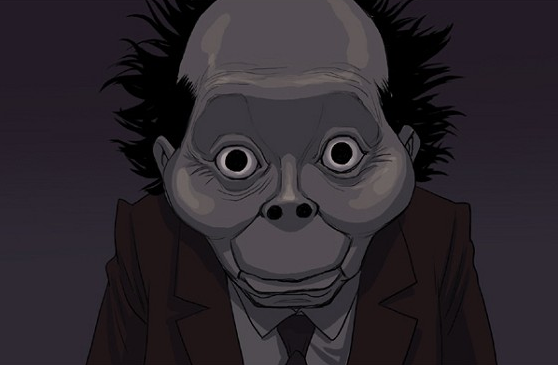

Villain Cheon Yongdeok from Moss (credit: Moss/The Huffington Post)

HGL: Do you have plans to translate other webtoon titles?

BJCF: Yes. For our translation of Moss we formed a partnership directly with Yoon and his company (rather than a pay-by-the-word arrangement with Rolling Story). Our approach during 35 years of translation of modern Korean fiction has been to focus in depth on a select few authors over the decades, and we envision a similar relationship with Yoon Taeho. We’re especially interested in his manhwa that are retellings of classic Korean stories and/or works that can appeal to an international audience.

As to titles by other manhwa creators, we’re not so sure. From what we’ve seen of the other webtoons being carried by the Huffington Post, we don’t see much difference from Japanese manga. We prefer an author/artist with a distinct style.

About the Interviewees:

Bruce and Ju-Chan Fulton are the translators of numerous volumes of modern Korean fiction, including the award-winning women’s anthology Words of Farewell: Stories by Korean Women Writers (Seal Press, 1989) and, with Marshall R. Pihl, Land of Exile: Contemporary Korean Fiction, rev. and exp. ed. (M.E. Sharpe, 2007). Their most recent translations are The Moving Fortress by Hwang Sunwŏn (MerwinAsia, 2015), the graphic novel Moss by Yoon Taeho (serialized at the Huffington Post, 2015-present), and several entries in the ASIA Publishers bilingual editions of modern Korean short fiction. Bruce is the inaugural holder of the Young-Bin Min Chair in Korean Literature and Literary Translation, Department of Asian Studies, University of British Columbia.

Links:

- Yoon Taeho, Moss (Ikki), translated by Bruce and Ju-Chan Fulton, at Huffington Post.

- Mary Ann Gwinn, “Bruce and Ju-Chan Fulton bring Korean literature to the English-speaking world,” Seattle Times, May 16, 2010.

- Michał Borodo, “Multimodality, translation and comics,” Perspectives: Studies in Translatology, 23, no. 1 (2015): 22–41.

- Yeon-Kug Moon, Hee-Hwa Yoon, Sung-Hun Chae, Dong-Hyun Lee, “Design of the Webtoon term processing engine to support automatic translation for Korean webtoon text,” Association of Electronic Engineers of Korea (2015): 1484-1486. (Korean) 문연국, 윤희화, 채승훈, 이동현「한국 웹툰 텍스트의 자동 번역 지원을 위한 웹툰어 처리 엔진 설계」『대한전자공학회 학술대회』(2015): 1484-1486.

- Chang-Wan Han and Nan-Ji Hong, “Storytelling for Converting Webtoon Into Movie: The case of Moss,” Journal of the Korea Contents Association, 11, no. 2 (2011): 186-194. (Korean) 한창완, 홍난지「웹툰의 영화화를 위한 스토리텔링 연구 – 웹툰〈이끼〉의 스토리텔링을 중심으로」『한국콘텐츠학회논문지』11, no. 2 (2011): 186-194.

- Hyung-Gu Lynn, “Korean webtoons: explaining growth,” Research Center for Korean Studies Annual – Kyushu University, 16 (韓国研究センター年報) (2016): 1-13.

- Dal Yong Jin, “Digital convergence of Korea’s webtoons: transmedia storytelling,” Communication Research and Practice, 1, no. 3 (2015): 193-209.

Related Memos:

See our other memos on South Korea.