Memo #363

By Jeffrey Wasserstrom – jwassers [at] uci.edu

Which past leader of a one-party state is Xi Jinping most like?

When he took power in 2012, some expected his rule to resemble that of Hu Jintao, his predecessor – a bland technocrat uninterested in shaking things up. Others suggested he might morph into a liberalizer, perhaps even becoming the closest thing to a reincarnation of Zhao Ziyang, the reformist purged in 1989. Xi has proved more colorful and forceful than Hu, and more interested in tightening than loosening controls, prompting additional comparisons. Some call him a new Deng Xiaoping or a throwback to Mao Zedong.

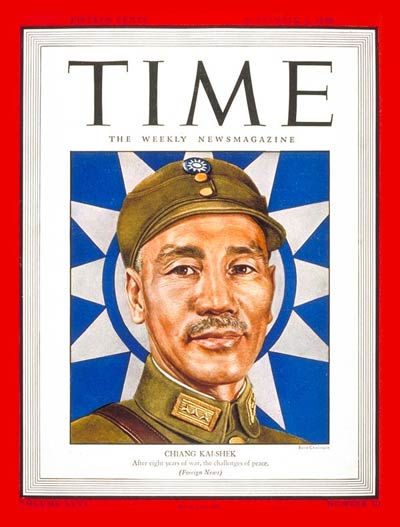

A compelling alternative answer to the original question, though, lies further back in history. For Xi has much in common with Chiang Kai-shek, the Nationalist Party strongman who ruled the mainland until Mao’s Red Army drove him into exile on Taiwan.

First, when Xi makes diplomatic trips accompanied by his glamorous wife, the forays abroad that Chiang made with his stylish spouse come to mind. Second, Chiang, like Xi, had little tolerance for dissent or interest in political liberalization.

Third, China’s current leader’s fondness for toggling between quoting Mao, a recent radical, and praising Confucius, an ancient conservative, also makes one think of Chiang. The Nationalist leader claimed that there was nothing inconsistent about his claiming to be carrying China forward along the path blazed by his revolutionary predecessor Sun Yat-sen, while venerating traditional Confucian values.

Fourth but not least, a key challenge Xi faces, and is striving to defuse via his much vaunted anti-corruption drive, is one that helped curtail Chiang’s rule of the mainland: the widespread perception that a small set of intertwined families have far too much wealth and power.

This analogy is, admittedly, an imperfect one. Xi does not have to deal with an armed opposition, for example, and China is in a stronger geopolitical position than it was seventy years ago. Still, there are similarities worth pondering—and also an irony if we bring Taiwan’s recent election into the picture. It’s hard to think of a time when Taiwan was less like it was when Chiang ran it, or when the mainland was more like it was under Nationalist rule.

About the Author:

Jeffrey Wasserstrom is Chancellor’s Professor of History at UC Irvine, Editor of the Journal of Asian Studies, and author, most recently, of Eight Juxtapositions: China through Imperfect Analogies from Mark Twain to Manchukuo, published later this month as a Penguin Special.

China’s leaders are featured on several decorative plates, (L-R) President Xi Jinping, Mao Zedong, Deng Xiaoping, Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao (Source: Greg Baker/AFP/Getty Images).

Chiang Kai-Shek featured on the September 1945 issue of Time magazine (Source: Time Inc).

Links:

- Jeffrey Wasserstrom, Eight Juxtapositions: China through Imperfect Analogies from Mark Twain to Manchukuo (e-penguin, forthcoming 2016).

- — ed., The Oxford Illustrated History of Modern China (Oxford: Oxford University Press, forthcoming 2016).

- — (with Maura Elizabeth Cunningham), China in the 21st Century: What Everyone Needs to Know, second edition (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013).

- AFP, “Chiang Kai-shek statues become targets as Taiwan confronts history,” Straits Times, August 2, 2015.

- Geremie Barmé, Jeremy Goldkorn, and Linda Jaivin, eds., China Story Yearbook 2014: Shared Destiny (ANU, 2014).

- The China Blog, Los Angeles Review of Books.

- Rob McBride, “China’s first lady dresses to impress,” Al Jazeera, March 28, 2013.

- Louise Watt, “Mao enemy Chiang Kai-shek gets new life in China’s mainstream culture,” Japan Times, August 18, 2014.

Related Memos:

See our other memos on China.

[…] seeing parallels between the city in question and Berlin. And then, more recently still, I wrote a juxtaposition-focused piece on Xi Jinping , placing him this time not beside a foreign figure but a figure from China’s past, Chiang […]