Memo #396

By: Nick Stember – nick.stember [at] gmail.com

Chinese manhua (literally, ‘casual pictures’) remain virtually unknown in Europe and North America, trailing Japanese manga in popularity even within mainland China. Though China has a long history of satirical cartoons and comic strips going back to the early 20th century, since the 1990s Chinese-originated comics and animated films have struggled to compete with foreign imports.

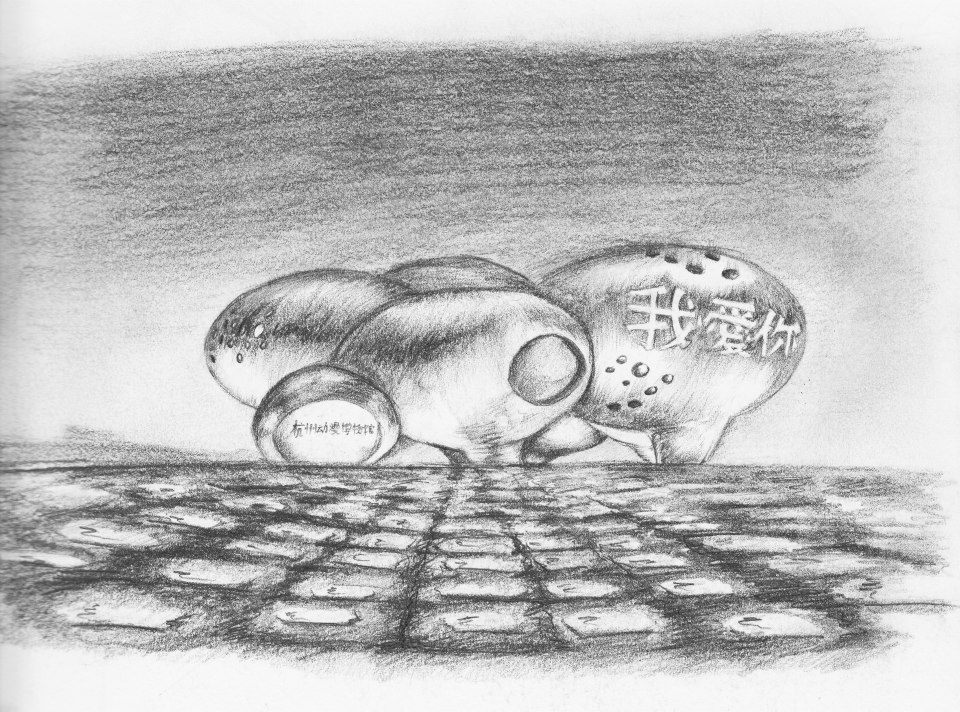

Cultural entrepreneurs in China are trying to change that, with Manhua impresario Tony Wong Yuk-long recently announcing plans to build a HK$800 million (~US$103 million) Chinese cartoon theme park in Hangzhou. Earlier Middle Kingdom-meets-Magic Kingdom efforts have had mixed success, however. The Shanghai Comic and Animation Museum opened in 2010, but a Chinese Museum of Comic and Animation project that began in 2011 with a budget of US$100 million remains unfinished.

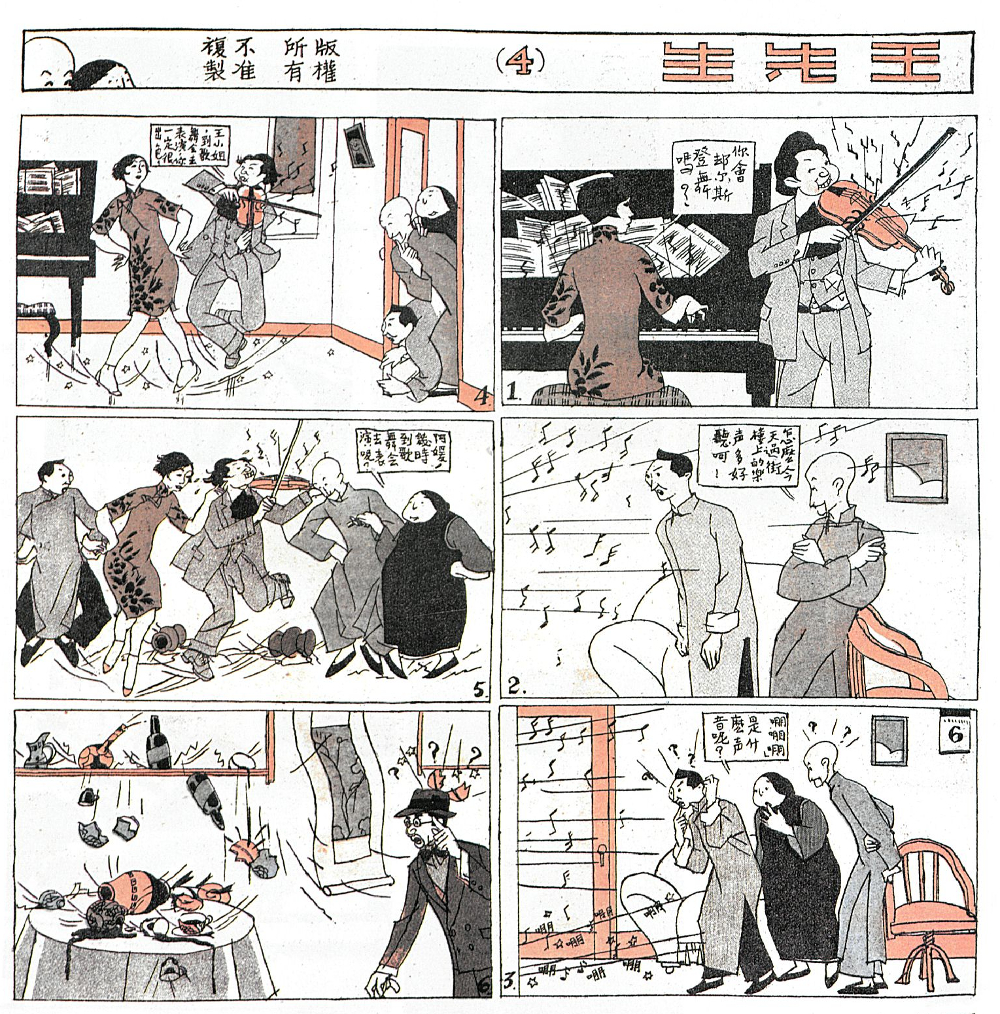

While such efforts are, in some respects, aimed at competing for future market share, there is also a desire to recapture a more glorious past. The 1930s is considered the first golden age of Chinese cartooning. From Ye Qianyu’s prototypical Shanghainese Mr. Wang, to Lu Shaofei’s Dr. Fix-It, manhua characters appeared in newspapers and magazines alongside ads for everything from toothpaste to ball gowns. In 1939, during the Anti-Japanese War, communist cadre and United Front propaganda bureau head Guo Moruo called for animated films to be made of Huang Yao’s clueless Ox-Nose and Zhang Leping’s orphan boy Three-Hairs, so that they may “…come alive like Mickey Mouse and Cinderella and Huang and Zhang will become Asia’s future Walt Disneys.” Two years later in Japanese-occupied Shanghai, the Wan brothers completed the first feature-length Chinese animated film, Princess Iron Fan, based on an episode from the Ming-dynasty novel Journey to the West. The state-sponsored Shanghai Animation Studio produced animated films for children and adults alike in the 1950s, and again after the Cultural Revolution.

While recent big budget state-sponsored animated films aimed at Sinophone millennials have struggled to find an audience, lighter fare such Alice Mak’s McDull and Huang Weiming’s Pleasant Goat and Big Bad Wolf have become icons of the Chinese animation industry. It remains to be seen whether these series represent harbingers of a greater revitalization of Chinese cartooning, or a new normal of diminished expectations for an industry facing the twin challenges of censorship and piracy.

About the Author:

Nick Stember completed his Master of Arts in Asian Studies at the University of British Columbia in 2015 and is a professional translator of Chinese literature and comics.

Fourth Mr. Wang strip by Ye Qianyu, from Shanghai Sketch Issue #3, published May 5, 1928.

Concept drawing for the Hangzhou Chinese Museum of Comic and Animation by Peihue for AAD 180.

Links

- Nick Stember, “Don’t Call it ‘Manga’: a short intro to Chinese Comics and Manhua,” March 19, 2014.

- Vivienne Chow, “’Little Rascals’ head to Hangzhou: Hong Kong comic king plans a HK$800m theme park far from home,” South China Morning Post, December 3, 2013.

- Joe McCulloch, “A Beginner’s Guide to Jademan,” The Comics Journal, July 1, 2014.

- Nick Stember, “A Comics Industry with Chinese Characteristics: Manhua Publishing in the PRC and Hong Kong,” April 15, 2015.

- John A. Crespi, “China’s Modern Sketch,” MIT Visualizing Cultures, 2011.

- Wan Laiming and Wan Guchan, Princess Iron Fan, 1941.

- John A. Lent, “Te Wei and Chinese Animation: Inseparable, Incomparable,” Animation World Network, March 15, 2002.